Translate this page into:

Failing to fail: MUM effect and its implications in education

*Corresponding author: Rajiv Mahajan, Department of Pharmacology, Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab, India. drrajivmahajan01@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Bhagat P, Virk A, Saiyad SM, Mahajan R. Failing to fail: MUM effect and its implications in education. Adesh Univ J Med Sci Res 2021;3:59-63.

Abstract

It is important to carry out the assessment of students correctly and in an unbiased way; but more importantly, the assessment decisions should also be conveyed to the students in an unbiased manner, even if the decisions are negative ones. But here lies the catch – many a times, assessors tend to shy away from conveying such negative decisions properly to the students due to various reasons. This article is an effort to identify such reasons and their implications in the education scenario.

Keywords

Assessment

Feedback

Competency-based medical education

Educational environment

Capacity building

INTRODUCTION

Now that we have shifted to competency-based medical education (CBME), we not only need to shift our focus on making successful learners but also to chart-out a plan – what happens when the learners stumble or fail.[1] With CBME, attention also has been significantly diverted from teaching methodologies to assessment strategies.

A robust assessment program should ensure that those who graduate are able to function as effective and safe clinicians. Assessment is a key component of any education program – it drives learning; provides students with valuable feedback to guide and promote their development; evaluates competence and ensures that set standards are met and allows or prevents student progress, for the benefit of both the student and the community; and also helps the educational institutions to review and improve their own performance. When weaved throughout a program, it can reduce the pressure of the final examination, if trainees have had more exposures to prior assessments followed by performance improving feedbacks; and can allow trainees in need of remediation or additional support to be identified earlier and also exit the course timely if their remediation is not possible or unsuccessful.[2]

Assessment in medical education has changed profoundly over the past few decades; has also introduced several challenges; and is influenced by many factors, all of which have the potential to jeopardize the validity of the assessment result. Some of the identified challenges are detailed in Table 1.

| Challenges | Description |

|---|---|

| Logistic and environmental | The need to assess trainees amidst clinics or wards or compensating for routine work adds to an already stretched schedule and may be often interrupted |

| Unstructured nature of assessments | This can lead to rater cognition, numerous biases, halo effect, and data organization and recall |

| Lack of training, experience, and motivation among assessors | Some assessors may not understand or embrace the occurring changes in assessment; some may be conscious of a conflict with their roles also as teacher, guide, and mentor while some may doubt the benefit of the assessment or perhaps that the result may even cause harm. There may be a general lack of enthusiasm to deliver an assessment message/result/feedback, especially when the message is negative |

| Unreceptive trainees | Trainees may not always accept the feedback they are given, especially if it differs from their self-assessment and more so when negative messages are involved |

An important aspect of any effective assessment system is timely and honest feedback to the students. But does that always happen? Even if we ignore the lack of expertise factor, documented literature shows that assessors deliberately choose not to communicate the feedback honestly to the students – they prefer to keep “MUM.” This write-up aims to not only understand this “MUM effect” but also suggests strategies to overcome them.

MUM EFFECT

The human brain processes positive and negative information in separate cortical areas. Furthermore, communicators appear to share good news quite uniformly but bad news with much variation. Therefore, in general, individuals exhibit greater reluctance to share bad news compared to good news.[3] In the education scenario too, the assessment of medical trainees’ performance aims to provide them with accurate and meaningful information and guidance on their learning and developing competence but arriving at the correct assessment result is only one part of an assessor’s duty. The result must then be delivered in the required manner to the trainee and institution. At times, the assessor may not deliver their intended message as required, especially if negative, in full or part, with either avoidance or delay or distortion. This results in “failure to give feedback,” “grade inflation,” and/or “failure to fail;” phenomena collectively known as the “MUM” effect, that is, keeping Mute about Undesirable Messages or Minimizing Unpleasant Messages.

When an assessor knowingly elevates a student’s attainable grade or rating, it is termed “grade inflation” and when a trainee who is otherwise unable to reach the required standard is passed, it is termed “failure to fail,” initially called a “teacher’s dilemma.”[2]

The term “MUM effect” was first coined by Rosen and Tesser in 1970;[4] and identified and introduced to the medical education literature by Williams et al. in 2003.[5] Understanding the MUM effect could help medical educators to improve assessment in health professions education.[6]

WHAT ARE THE MANIFESTATIONS OF MUM EFFECT?

Reluctance to deliver negative assessment messages which can result in failure to give feedback, failure to fail, and grade inflation is a real and continuing issue in medical education. There are three main ways these may manifest – Delay in giving the message, Avoiding giving the message, and Distorting or “sugar coating” the message;[2] collectively called “DAD effect” [Table 2].

| Manifestation of MUM effect | Consequence |

|---|---|

| Delay in delivering the message | The original message may get distorted and or may lose its effectiveness |

| Avoid delivering the message | The duty may be delegated to others |

| Distorting the message | Grade inflation or failure to fail |

| Deliver the message without any consequences | Deliver the message of record/through written comments/through marks |

The assessors may not communicate what they really think of the trainee’s performance or may not tell the trainee about the things that they did wrong or may even pass them when they should not be doing so. The mode of delivery can also affect the results delivered.

MUM effect is found to manifest more when assessors are required to give the assessment results directly to the trainees compared to giving results indirectly through writing only. An example is workplace-based assessments, where the trainee usually works with the assessor, and the result is often required to be delivered immediately and/ or without the opportunity to think about the performance or discuss it with someone. Furthermore, assessors fail to give comments in negative, written, or verbal, more commonly than failing to give negative grades/marks. The MUM effect may also vary with the possible outcomes of the assessment, that is, for summative assessments as compared to formative ones.

WHAT DOES THE MUM EFFECT MEAN FOR HEALTH PROFESSION EDUCATION?

MUM effect is universal. When the performance observed is of a high standard, delivery of the assessment result may be easy; but when it is poor, the delivery of that message may be challenging and the consequences may be profound for individuals and the institutions at large.

Without effective and accurate feedback, mistakes remain uncorrected, good performance is not reinforced and competence is achieved empirically or not at all. This results in loss of opportunities for the student for self-reflection, improvement, or remediation, thus predisposing them to the future assessment failures. The training institution is also denied feedback on its performance, thereby limiting its own development. “Failing to fail” sends a wrong message to the trainees that they are competent. When such trainees are undeservedly allowed to progress, patient safety gets compromised. MUM effect shows that “no news” is not necessarily good news.[2,6]

WHY DOES THE MUM EFFECT OCCUR?

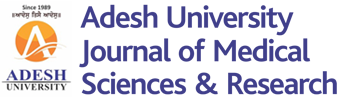

MUM effect occurs due to three main concerns – communicator’s self-concern, communicator’s concern for others, and communicator’s concern with norms[7,8] [Figure 1].

- Main reasons for the occurrence of MUM effect.

Overall, those who are engaged and committed to their role as assessor may show lesser MUM behavior compared to those who are reluctant or resentful of their role. The varied reasons and their possible solutions are highlighted in Table 3.[2]

| Reason | Possible solution |

|---|---|

| Inexperience as assessor | Assessor training |

| Difficulties with the scales used in tools | Use of entrustability scales |

| Inability to understand or embrace assessment changes | Assessor training |

| Considering failure as a negative notion | Change in thinking, to one of providing support and opportunity for improvement |

| Fear that negative feedback may cause harm/“stigmatization”/“penalization” of trainees | Availability of effective remediation options |

| Reluctance to face a “difficult conversation” with the trainee | Specific training of assessors based on their individual personality factors and tendencies to “MUM” |

| Consciousness of role conflict – as teacher, supporter and mentor, supervisor, and assessor | Assessor training Assigning independent assessors for the assessor role |

| Doubt about the actual benefit of assessments | Institutional transparency in program |

| Inclination to favor a trainee | Assessor training |

| Overall lack of motivation and willingness | Assessor training and continued support |

| Thought that trainee’s poor result reflects their own poor performance as teachers and supervisors | Assessor training and motivation |

| Lack of privacy or time for quality assessments | Institutional reforms |

| Concerns around legal repercussions or anticipation of an appeal or challenge to their assessment by trainee or being over-ruled by higher authority | Robust assessor training and support by institution and colleagues |

“MUM” effect reflects the “there is an elephant in the room” situation, where there is an obvious problem or difficult situation that people do not want to talk about, at least publicly.[9] However, lapses in performance are part of our daily life. Once we accept this fact and also that communicating “unpleasant” messages about such lapses can benefit both the lapsing person and future patient care, the teacher’s dilemma would be gone.[6]

ASSESSOR ROLE AND UTILIZING ASSESSMENT TOOLS EFFECTIVELY

One of the major reasons of MUM effect is, assessors are reluctant to communicate undesirable information to students as they fear psychological discomfort and potential damage to their image.[10] However, assessors have to remain flexible and adapt to all their roles.

In one study, when mentors were asked to choose the role they found most difficult to fulfill, most chose the role of assessor and evaluator as being the most difficult; stating that it was complex to separate the professional role of assessment from being a supportive friend and it was also hard to criticize students. None of them identified the role of assessor as an important part of “being a mentor.”[11] Biggest implication of “MUM” effect is – poor performance of learner may continue in absence of honest feedback hampering learning.

Feedback given by assessor, whether negative or positive goes a long way in improvement of learning of students. The utility of continuous, ongoing, authentic feedback based on direct observation of performance and given in an atmosphere of trust and in a non-threatening environment is profound.[12] The effect size of feedback is 0.79 among all the factors affecting students’ achievement and learning.[13] According to Kluger, both positive and negative feedbacks have beneficial effects on learning.[14] Hence, the effect of feedback on students depends on level at which feedback is aimed and processed than on whether negative or positive.[13] Giving negative feedback is trickier, but if done correctly, it can be highly effective. Furthermore, negative feedback is more powerful at self-level,[13] hence, apprehension of assessors regarding providing negative feedback is without reason. In fact, negative feedback, if delivered as constructive, useful, and effectively delivered, is well received and leads to better performance.

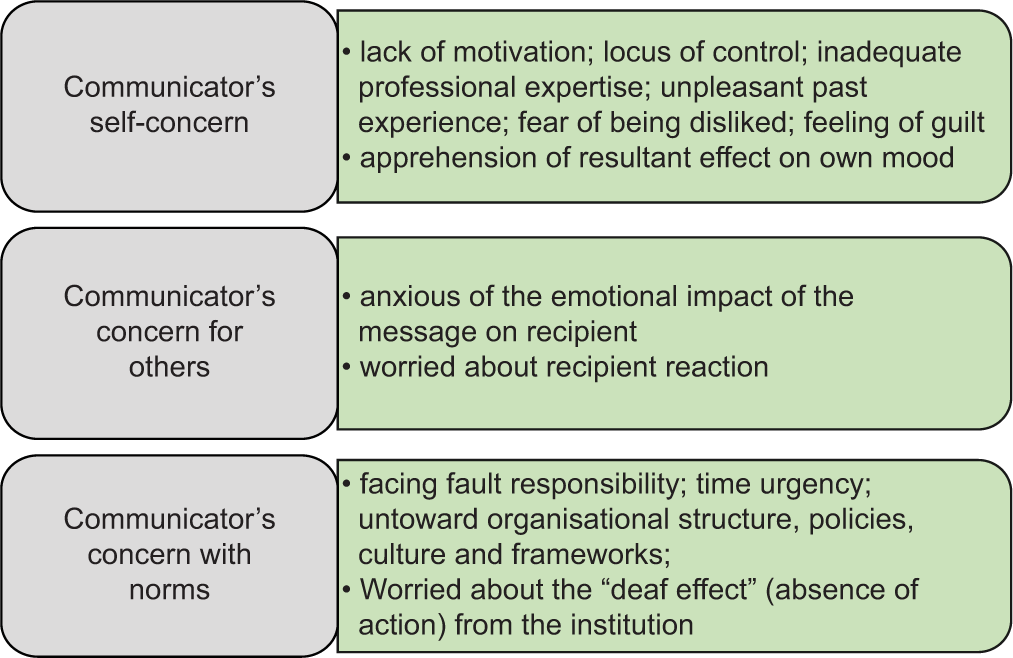

If feedback, whether positive or negative, is given taking into consideration a few tips, it is bound to be taken well by learners and “MUM” effect can be avoided. Do keep in mind that constructive criticism is best way to deliver negative feedback as it addresses both problem and solution. Although sandwich method of giving feedback is considered to be one of the most effective methods of feedback delivery, as it involves giving negative feedback tucked into positive feedback; however, in this method, sandwiching negative feedback can mask the actual feedback giving false rosy picture to learner. Hence, it is better to deliver honest feedback directly without sandwiching. Creating safe, trustworthy, and non-threatening environment for feedback can help in delivery of any type of feedback without discomfort to learner or assessor. Most importantly, specific and timely feedback should be provided to learners,[13] without any delay for facilitating learning [Figure 2].

- Tips for giving feedback to overcome “MUM” effect.

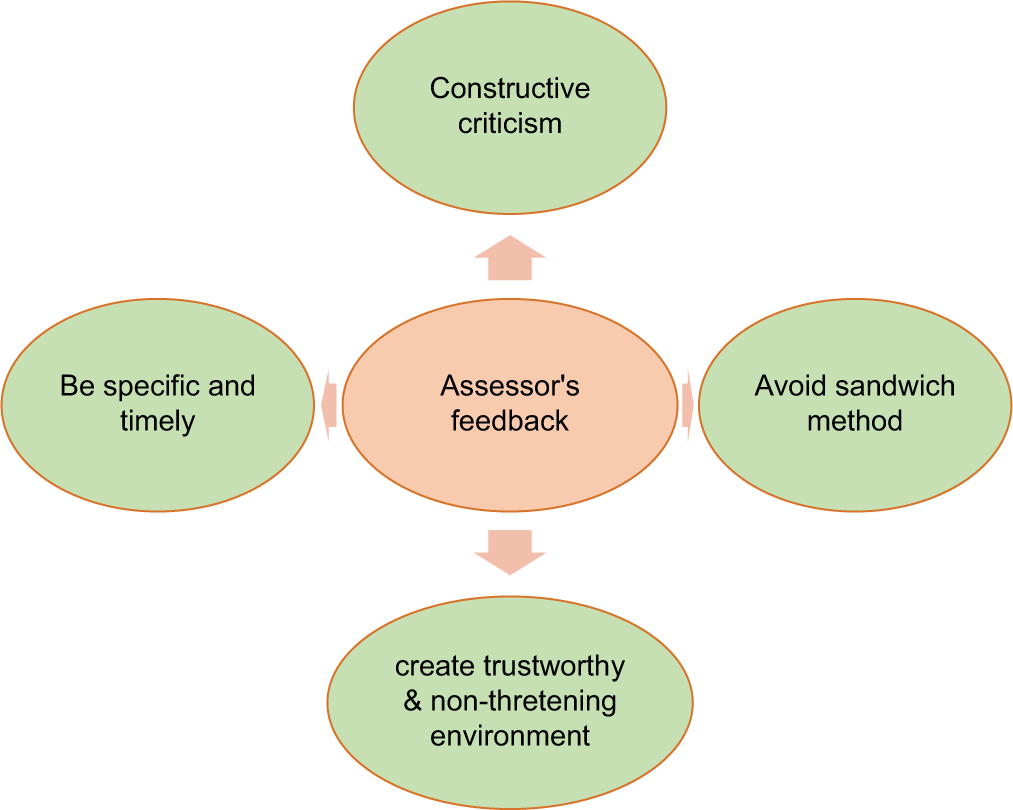

Kerns suggested DISC feedback tool to overcome “MUM” effect.[15] Although suggested for business models, it is relevant for health professions education too. The four steps of DISC tool are Describe, Impacts, Specify, and Consequences [Figure 3].

- Steps of DISC feedback tool.

Subjective assessment and judgments mean that the assessor’s experience is a necessary part of the equation and that different assessors can have different assessments of the same person. The teacher’s experience, therefore, becomes the assessment “instrument.” Assessor training is hence an indispensable part of any assessment program. The areas where a teacher’s capacity building needs to be addressed include making aware of one’s limits as assessor and possibilities of being biased, identifying the needed competencies, their performance expectations, measurement criteria in all relevant domains, design and use of assessment tools, and giving feedback to learners.

CONCLUSION

MUM effect is a reality in health professions education. As Boud rightly said – “Students can, with difficulty, escape from the effect of poor teaching. However, they cannot escape the effects of poor assessment”;[16] such an effect denies opportunities for effective feedback to the students. It also denies opportunities to take mid-course corrective measures. In short, it can jeopardize the effectiveness of entire assessment system and can put the reputation of an institute at risk.

References

- Situating remediation: Accommodating success and failure in medical education systems. Acad Med. 2018;93:391-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeping mum in clinical supervision: Private thoughts and public judgements. Med Educ. 2019;53:133-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaking good and bad news: Direction of the MUM effect and senders' cognitive representations of news valence. Commun Res. 2010;37:703-22. Available from: https://www.citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.906.2260&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]. 10.1177/0093650209356440

- [Google Scholar]

- On reluctance to communicate undesirable information: The MUM effect. Sociometry. 1970;33:253-63.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive, social and environmental sources of bias in clinical performance ratings. Teach Learn Med. 2003;15:270-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 'Failure to fail': The teacher's dilemma revisited. Med Educ. 2019;53:108-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Reluctance to Transmit Bad News. 2021. Available from: https://www.coek.info/pdf-the-reluctance-to-transmit-bad-news1-.html [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- A framework to manage reluctance to bad news reporting on software projects in state universities in Zimbabwe. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2020;25:5549-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessor Grades and Comments: Private Thoughts and Public Judgements. 2020. Available from: http://www.hdl.handle.net/11343/237446 [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- The reluctance to transmit bad news: Private discomfort or public display? J Exp Soc Psychol. 1987;23:176-87.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessor or mentor? Role confusion in professional education. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27:848-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of feedback on learning. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56:733-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:254-84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assertive Performance Feedback. 2010. How do You Find the “Backbone” to Overcome the “Mum Effect”? Graziadio Business Review. Available from: https://www.gbr.pepperdine.edu/2010/08/assertive-performance-feedback [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03]

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment and Learning-Unlearning Bad Habits of Assessment. Presentation to the Conference 'Effective assessment at University': University of Queensland; 1998.