Translate this page into:

Opioids: Boon or bane? It does not matter! A clarion call for opioid sparing strategy

*Corresponding author: Mridul Madhav Panditrao, Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences & Research, Adesh University, Bathinda, Punjab, India. drmmprao1@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Panditrao MM. Opioids: Boon or bane? It does not matter! A clarion call for opioid sparing strategy. Adesh Univ J Med Sci Res. 2024;6:79-85. doi: 10.25259/AUJMSR_9_2025

Abstract

“Opioids” have always been considered as an absolute and irreplaceable necessity for the ‘intra as well as postoperative analgesia’. Such is the ‘dependence’ of clinicians on them, especially the anaesthesiologists, that no matter what modality of anesthesia, general or regional, is being planned, opioids are included overzealously. However, it is beyond doubt that their side effects and complications can be severe and long-lasting. Almost the entire world is going through the ravages of what is called as ‘opioid crisis/prescription induced opioid addiction epidemic’, which has claimed thousands of victims, not only in the form of mortality but also severe and life-long morbidity, destruction of families, unraveling of social fabric and increased criminality. In the Western world, what started as initially the street heroin problem now has fully blown out and evolved into a prescription ‘fentanyl’ abuse challenge. Back home, in our northeastern states, it is heroin, while in the northern states of Punjab and Haryana, along with heroin, there is a silent killer, which is invading and destroying the society- Tramadol! For this, in the first place, we clinicians are responsible for unwittingly prescribing it and inadvertently exposing the novice/newer generation to this ‘over the counter, dangerous drug. . Later on these ‘exposed’ individuals fall prey to drug-seeking habit. Entire generations of men and women have gone on the way of becoming ‘silent addicts’! There is an urgent need to introspect, reorient and reprogram our therapeutic planning. “Opioid sparing strategy (OSS)” is an absolute need of the hour. The most suitable alternative would be ‘Multimodal anesthesia/analgesia (MMA)’. This concept is not new, but there have been some radical changes in its implementation and execution. Newer therapeutic agents, newer techniques and permutations and combinations of these modalities is one of the most plausible ways out of this crisis!!

Keywords

Multimodal anesthesia

Opioid sparing strategy

Prescription-based “Opioid addiction epidemic”

Problems of opioids

Suitable alternatives

INTRODUCTION

Opioids are beautiful “drugs!”

For both, the patient as well as the Clinician.

They are the “Boon” for any doctor who deals with pain, especially for anesthesiologists, orthopedicians, oncosurgeons, pain specialists, and of course for the patients suffering from pain.

Predictable, potent, reliable, and effective.

Their analgesic spectrum is unquestionably wide and generous. Some philosophers have eulogized them as:

“Among the remedies which it has pleased Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium.”[1]

The famous and often-quoted words of British physician Thomas Sydenham (1680) aptly glorify them.

Sir William Osler has equated morphine as “God’s Own medicine” after himself being treated with morphine for two attacks of renal colic.[2]

Such has been the aura of these drugs. Opioids have long been the “Gold Standard” for managing acute and chronic pain, especially in post-surgical, cancer, and palliative care settings. Their efficacy in providing rapid pain relief is undisputed, and they remain a cornerstone in pain management protocols worldwide. In most of the guidelines for the management of acute/chronic pain, opioids are ubiquitous, all-pervading and so-called an “indispensable evil.” Their presence is mandatory in most of the protocols of anesthetic managements, irrespective of whether balanced general anesthesia (BGA) or regional techniques. We tend to prescribe and administer the opioids almost overzealously.[3]

OPIOIDS: WHY DO WE ADMINISTER THEM AS A CONSTITUENT OF BGA?

BGA, is comprised four main components, that is, 4 “A”s: Analgesia (anti-nociception), amnesia (unawareness), areflexia (absence of autonomic reflex activity), and akinesia (muscle paralysis).[4] Strategically, the basis of the action of the pharmaceutical agents employed for achieving BGA is at the mu, kappa, delta-opioid receptor (MOP, KOP, and DOP) family systems, and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptors, either of them or the combination of them.[5] Starting from induction of anesthesia till the patient is discharged from the hospital after recovering, these receptors are being targeted by the drugs like intravenous induction agents/inhalational agents on GABA-A while opioids like morphine, fentanyl acting on either or all of the opioid receptor families.

Presently, all over the world, the opiates (synthetic or manufactured opioid analgesics) are well entrenched as the routinely and most commonly used medications to achieve the intraoperative and post-operative analgesia (control of nociception in the perioperative period). Undoubtedly, nociception is the main reason for autonomic hyperactivity, leading to hemodynamic and psycho-behavioral changes culminating in the emergence of post-operative chronic pain syndromes.[5] The efficacy of opioids in inhibiting autonomic responses and thus controlling hemodynamic disturbances is evidently confirmed.[6-8]

Indisputably, we consider opioids to be the essential commodities to produce intraoperative analgesia (antinociception) and then continue the same as postoperative analgesia. Paradoxically, we assume both the phenomena, as the continuation of the same spectrum, which is fundamentally incorrect. Pain, especially in the post-operative period, is purely a subjective sensation perceived by the individual in their conscious state, while intraoperative antinociception produced by blocking the ascending nociceptive impulses, as discussed above, is mainly the control of autonomic pressor responses/hemodynamic disturbances to the surgical stimuli, under “BGA.”[3] In addition, some more benefits may be attributed to the use of opioids such as,

Decreasing the requirement/doses of intravenous/inhalational agents

Minimizing their negative effects on hemodynamics and

Thus, maintaining overall cardiovascular stability, inclusive of adequate coronary circulation,

Depressing central respiratory drive and thus facilitating the mechanical ventilation, minimizing the requirement of neuromuscular blocking drugs.

THE DARK SIDE OF OPIOIDS: DELETERIOUS EFFECTS

This is only one side of the coin. Not everything is hunkydory about them.

-

With more emerging evidence, it is amply clear that the perioperative administration of opioids, especially in higher doses, may have deleterious effects, like heightened pain perception and, logically, increased demand for postoperative opioids.[9] The primary reason for this is opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia.[8,10]

Tolerance is the gradual decrease in the response of the opioid with the same dose after its chronic use over days/weeks. In other words, effectively, to achieve the same response, the dose to be administered has to be increased. This is chronic desensitization.

Hyperalgesia is defined as extremely heightened sensitivity to pain, disproportionate to what otherwise would be expected.

All the opioids are capable of producing both the responses, especially the ones with shorter action like fentanyl.[11] In addition, opiates/opioids are shorter-acting agents relieving somatosensory/visceral pain but are not so effective in neuropathic types of pain.

In addition, the well-documented minor ones like pruritus and skin rashes secondary to histamine release, mainly with morphine,

Major concerning side effects like post-operative nausea vomiting (PONV) a major problem in patients undergoing oto-rhino-laryngological, neuro, and eye surgeries (can undo the whatever, the surgeon has done),

Urinary retention, many a times necessitating the catheterization and precipitating possible urinary tract infection.

Gastro-intestinal (GI) complications such as gastroparesis, biliary stasis, paralytic ileus, and GI distention, can cause long-term deleterious effects.

GI distention in the postoperative period tends to push the hemidiaphragms more into the thoracic cavity, leading to atelectatic consolidation of basal regions of the lungs, increased shunt fraction, decreased gaseous exchange, hypoxia, and its consequences, like, increased work of breathing, and increased chances of reintubation and restarting and prolongation of mechanical ventilation.

The GI inactivity (gastroparesis) also interferes with the initiation of enteral nutrition, as there is decreased emptying of the stomach, would be no forward movement, precipitating catabolism, negative nitrogen balance and further consequences, like sepsis, wound dehiscence.

One of the most common complications, which needs to be anticipated is post-operative central/respiratory depression leading to respiratory failure, manifesting as decreased respiratory rate as well as decreased respiratory excursions, leading to respiratory depression and death.[12] It can happen even in normal adults in the immediate postoperative period but is of common occurrence in predisposed patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, preexisting sleep apnea syndrome, and upper GI surgeries.

The immunosuppressant effects of chronic opioid use and its consequences in cancer patients need to be remembered.

The opioid crisis has led to immense healthcare costs, workforce losses, social instability, and increased socioeconomic burden.

“Addiction and Dependence:” Chronic use can lead to physical dependence and opioid use disorder (OUD).

Unfortunately, these are downplayed, ignored or majority times not even considered of any consequences by the treating physician, while prescribing them.

INTROSPECTION NEEDED WHILE PRESCRIBING OR ADMINISTERING OPIOIDS: DO WE EVER SERIOUSLY CONSIDER THE DELETERIOUS EFFECTS THEY MAY OR WILL PRODUCE?

All of this discussion is evidently acceptable and also undebatable. However, the moot question, which needs to be answered, remains: “Do we seriously consider the possible deleterious effects of opioids while administering them?” Unfortunately, the majority of times, the answer would be “NO.” Not because we are not aware of them but because of the wrong and misconceptual prioritization of our objectives, like

Well-entrenched old teachings of a liberal use of opioids for intraoperative anti-nociception to be continued as the post-operative analgesia.

Overzealousness and non-standardization of postoperative pain management protocols and

Ignorance about the suitable, safer, and more efficient alternatives available,

Last but not the least, by rote, or just as a routine.

We tend to gloss over the side effects/complications of the opiates.

WHAT IS “OPIOID ABUSE CRISIS” OR PRESCRIPTION BASED GLOBAL OPIOID ADDICTION EPIDEMIC?

“At first, addiction is maintained by pleasure, but the intensity of pleasure gradually diminishes, and the addiction is thus maintained by avoidance of pain.”

Frank Tallis (aka, Francesco de Nato Napolitano)[13] English author and Clinical Psychologist (Author of the famous “Lieberman Papers” and “Vienna Blood”)

The widespread misuse of opioids has led to an epidemic of addiction, overdoses, and deaths. According to public health data, opioid-related fatalities have skyrocketed, particularly in regions with high prescription rates. The crisis has also imposed a significant economic burden on healthcare systems and society, with costs related to emergency care, rehabilitation, and loss of productivity.

OPIOID ABUSE CRISIS/OPIOID ADDICTION EPIDEMIC OF NORTH AMERICA’S/INDIA

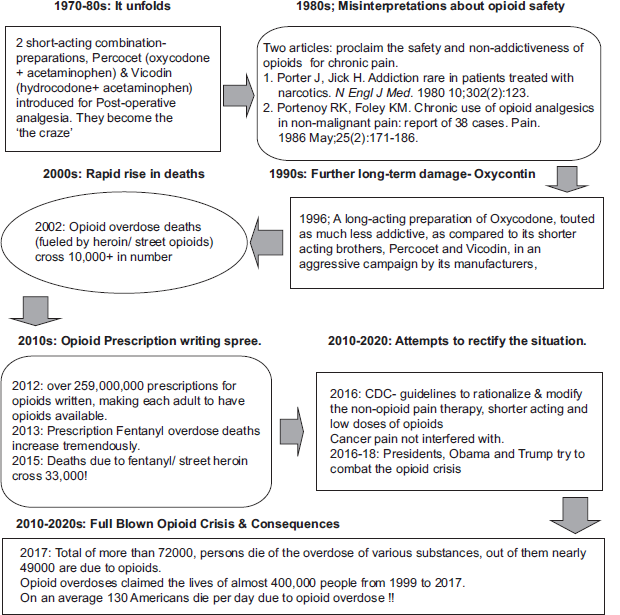

The worst outcome which has emerged out of this strategy of indiscriminate perioperative opioid use, has undoubtedly been the high potential for and obvious development of opioid addiction. This has evolved into a full-blown opioid addiction crisis, which has ravaged the western world. What started as a simple prescription spree has gone out of control into a national and now a global calamity. Figure 1 depicts the chronology and unprecedented rampaging progression of the prescription induced opioid crisis in the United States of America (USA).[14] Although the chronology has been traced till 2017, the mortality and destruction of life continues relentlessly. As shown in the figure, more than 400,000 individuals have died in the past two decades in USA alone and more than 600,000 in both USA and Canada and as per an editorial in Lancet, an estimated 1.2 million people could die from opioid overdoses by 2029. (Lancet; Editorial: March 01, 2022).[15] Fentanyl has emerged as the most prominent cause. There are recent reports of accidental deaths of the infants and toddlers of the fentanyl addict parents, who have died due to the accidental exposure to the drug scattered by the parents on the fomites, furniture and even milk bottles of these pediatric victims. The lawmakers are demanding penalty against the parents under the penal sections of homicide.[16] Such an alarming is the situation in the USA.

- Algorithmic depiction of chronology of the prescription-induced opioid addiction crisis.

India is not far behind. A survey report from Ministry of Social Justice of Government of India (GOI), in 2019, reported some interesting figures.[17] About 2.1% of the country’s population (2.26 crore individuals) uses opioids, which include opium (or its variants like ground dried poppy husk known as Doda/bhukki), heroin (or its impure form – smack or brown sugar) and a variety of pharmaceutical opioids. Nationally, the most common opioid used is heroin (1.14%) followed by pharmaceutical opioids (0.96%) and opium (0.52%). Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, and Mizoram have the highest prevalence of opioid use in the general population (more than 10%). Out of the estimated approximately 77 lakh people with OUDs (harmful or dependent pattern) in the country, more than half are contributed by just a few states: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, and Andhra Pradesh. However, in terms of the percentage of population affected, the top states in the country are those in the north east (Mizoram, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, and Manipur) along with Punjab, Haryana, and Delhi.[17]

“TRAMADOL MENACE, PECULIAR TO INDIA (ESPECIALLY NORTH/NORTH-EAST)”

After reading such reports, one would be misled to congratulate oneself, that, the “substance abuse,” especially, opioid abuse crisis in India is not similar to USA or European countries, namely, the prescription-based abuse, rather it is more of a “street based” pattern with more dependence on heroin. That would be far from true, because it appears like we, especially in Northern states of Punjab and Haryana are almost following the similar pattern, as shown in Figure 1, as at the 1970–80s level, in USA (introduction of Percocet and Vicodin). Except that, the drug, which is inadvertently and indiscriminately being prescribed by almost every clinician, including, anesthesiologists, obstetricians, orthopedicians, and even general/family physicians and in the rural areas, especially in northern states by so called “registered medical practitioners’ (RMPs), a sophisticated name given to the quacks, is “Tramadol.” There are multiple number of reports about this nascent monstrous problem, for which we, the clinicians should be considered as the culprits. There are various published reports, one of them a bold proclamation by the Punjab-Haryana High Court judge,[18] prominent news media house report,[19] another a publication from the legal fraternity,[20] about the potential “excessive use (misuse/abuse)” of tramadol and we are sitting on a “ticking time bomb” of the potential/almost there, looming opioid abuse crisis in the developing countries, especially, Northern India. A report from USA, aptly titled “The Dangerous Opioid from India,” puts the onus of responsibility for this drug on the lackadaisical policy of the GOI in relation with production, supply, prescription policy, and over the counter availability of tramadol.[21]

The probable chronology with regard to tramadol, in our country, emerges as follows:

“A patient undergoes a routine abdominopelvic surgery under spinal analgesia, for example, total abdominal hysterectomy, herniorrhaphy, or under BGA, for example, laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In the immediate postoperative period as a part of some convoluted, “standard and routine” protocol, all the patients are administered the inj. Tramadol, 75 or 100 mg, by the concerned admitting team junior resident or the staff nurse, without consulting the pain physician/anesthesiologist. In fact, many anesthesiology trainees may also prescribe the same, without understanding the consequences. The patient gets mild to moderate relief, and may have some side-effects like PONV, and pruritus, but these are considered as unavoidable issues and are treated symptomatically. The patient keeps on getting the drug, initially as injectable form later on maybe tablets. It has been proven beyond doubt, that due to its novel chemical makeup, the oral form of tramadol has more potential to produce “high,” as compared to injectable form.[20] By the time the patient gets discharged, he/she is “hooked” on to the drug. Even after going home, the drug-seeking habit keeps them pushing toward actual habituation/frank addiction.”

or

“A patient with acute/chronic pain (back pain, cervical pain, and vague abdominal pain), goes to actual doctor, or specialist (Orthopedicians, physician, pain specialists, and anyone) or better still, as happens the majority of times in our villages/smaller towns in Punjab/Haryana, to the “RMPs/quacks.” Conveniently, he/she is prescribes Tab. Tramadol and the same above-mentioned process gets repeated. A whole new batch of potential “tramadol abusers” has been created. Now, this patient has understood that, by feigning, non-relief of the pain, they keep on getting uninterrupted supply of tramadol. Over and above all this, whole system, (we have the unscrupulous, unethical, and immoral medical shop-owners, who in the greed of lucre). Go out of the way to deal in these drugs and supply them to the abusers/addicts.”

As would be expected in our country, there are no actual figures available, but it is estimated that, a significant number of youth in Punjab, Haryana, and other north/northeastern states have been gripped by the drug. And unfortunately, this is spreading like wildfire all over the country.

“The priority of any addict is to anesthetize the pain of living to ease the passage of day with some purchased relief.”

Russel Brand an English actor, comedian, and ex-addict

WHY THE DEBATE OVER OPIOIDS IS MISGUIDED

The opioid crisis has been a subject of intense debate, with some hailing opioids as a medical “Boon” for pain management and others condemning them as “Bane:” a public health catastrophe. This debate often falls into extremes – either as life-saving pain relievers or as dangerous substances fueling a global crisis. However, rather than engaging in a binary discussion of their benefits and risks, the focus should shift toward a pragmatic solution:

How can we reduce opioid reliance while still ensuring adequate pain management?

How to use them judiciously and supplement them with safer alternatives whenever possible?

This approach seeks to optimize pain management while minimizing opioid dependence, addiction, and associated harms. This calls for an opioid-sparing strategy (OSS), a balanced approach that reduces opioid reliance without compromising patient care.

THE OSS: A MULTIFACETED APPROACH

After understanding the fundamental and ugly dynamics of genesis and progression of opioid crisis, we have to reorient ourselves while dealing with our patients in the perioperative period.

An OSS seeks to minimize/reduce opioid exposure while ensuring effective pain management. This approach involves a combination of pharmacological, especially alternative medications, and non-pharmacological interventions tailored as patient-centered care.

“Opioid free anaesthesia/analgesia. (OFA) as a part of OSS is conceptually an effort or ideology/technique – where NO intra/post-operative systemic, neuraxial, or intracavitary opioid is administered with the anesthetics, thus avoiding the well-documented and obvious, what is called as “opioid-related adverse effects.”[12] In some of the techniques of OSS, small amount of opioid may be permissible, while keeping a strict monitoring about it.[22,23]

Fundamental principles are:

Primary principle: “Do not expose novice/non-exposed individuals to ‘opioids’!”

Reorient our understanding about the concepts of pain and its perception and modulation and bring it into our daily anesthetic/clinical practice.

Not to equate intraoperative analgesia (antinociception), same with the perception of post-operative pain sensation.

By influencing various neuromodulators (serotonin/5HT, n Methyl d Aspartate (NMDA), gamma-aminobutyric acid, acetylcholine, dopamine, and central noradrenaline) other than, the ones influenced by opioids (endorphins, enkephalins, dynorphins….so on and so forth), can we achieve the antinociception? Yes we can.[23]

Employ these therapeutic agents, which act on various other neurotransmitters/neuromodulators, to achieve opioid sparing/opioid avoidance and thus provide adequate post-operative analgesia, avoiding the deleterious side effects of opioids.

Reliance on a “sole/one drug would be counterproductive,” as “one” drug will not/cannot replace the opioids, so the use of multiple drugs which act in tandem, complimenting each other and thus decreasing the requirement of their dosages and decreasing the side-effects and complications of individual drugs, is recommended.

Employ multiples of modalities of administration of these drugs, and various routes of administration to achieve optimum intra- as well as post-operative analgesia.

Circumspectively, these are the principles of Multi-Modal Anesthesia/Analgesia (MMA).

So essentially, we are discussing the employment of MMA as OSS/OFA!!

WHAT IS MMA? – A LAYERED APPROACH TO PAIN MANAGEMENT

Multimodal analgesia involves combining different pain-relief methods, like combination of medications that act on multiple pathways, reducing the need of opioids. Key components include:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Ketorolac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib can reduce inflammation and pain.

Acetaminophen (Paracetamol): Effective for mild-to-moderate pain and can enhance the effects of other analgesics.

Gabapentinoids (Gabapentin and pregabalin): Useful for neuropathic pain.

Local anesthetics: Preservative-free lidocaine infusions

Nerve blocks (neuraxial, regional, or peripheral) can provide targeted pain relief.

NMDA receptor antagonists (Ketamine and magnesium): Used in certain settings to provide pain relief and prevent opioid tolerance.

Centrally-acting alpha-2 agonists (Dexmedetomidine and clonidine): Latest entrants in the arena.

Steroids (Dexamethasone): Effective against PONV, fatigability.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Beyond medications, various non-drug approaches have proven effective in reducing pain and opioid dependence, including:

Physical therapy: Strengthening and mobilizing affected areas to reduce pain.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy: Helping patients manage pain perception and coping mechanisms.

Acupuncture and massage therapy: Complementary techniques that may help alleviate chronic pain.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: A noninvasive method to modulate pain perception.

Personalized and patient-centered pain management plans

A one-size-fits-all approach to pain management is ineffective. Each patient’s pain experience is unique. Instead, healthcare providers should develop personalized pain management plans which can optimize outcomes and reduce the opioid exposure by:

Assessing individual pain profiles, especially type/severity and risk factors, to determine the most appropriate intervention.

Educating patients on realistic pain expectations and alternative pain relief methods.

Implementing close monitoring and reassessment to adjust treatment as needed.

Policy and prescribing reforms

To implement an effective OSS on a broader scale, systemic changes are required:

Revised stricter prescribing guidelines: Encouraging the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration.

Prescription drug monitoring programs: Tracking prescriptions to prevent misuse.

Enhanced physician and provider training: Ensuring medical professionals are trained in alternative pain management techniques.

Research and Innovation: Investing in novel pain relief modalities to reduce opioid reliance.

Revised prescribing guidelines: Encouraging physicians to prescribe the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration.

Prescription monitoring programs: Tracking opioid prescriptions to prevent misuse and over-prescription.

Enhanced physician training: Ensuring healthcare providers are equipped with knowledge on opioid alternatives and multimodal pain management.

A CALL TO ACTION

The opioid crisis is not a problem with a single solution and debating whether opioids are good or bad misses the point. It demands action, not just discussion. The real challenge is how to balance pain relief with patient safety, especially in the face of full-blown global prescription based opioid abuse crisis. OSS and by extension, OFA – grounded in MMA, non-drug therapies, personalized care, and systemic reforms – offers a practical path forward. The true focus should be on responsible pain management through OSS that ensures effective relief while reducing harm. Policymakers, healthcare providers, and patients must work together to adopt evidence-based approaches that prioritize both safety and efficacy.

The time for change is now – opioid sparing is not just an option; it is an imperative!

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Mridul Madhav Panditrao is on the Editorial Board of the Journal.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The author confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Why patients in pain cannot get “God's own medicine?”. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. 2014;5:81-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William Osler, urolithiasis, and God's own medicine. Urology. 2009;74:517-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multi-modal anaesthesia/analgesia as opioid-free anaesthesia/analgesia (MMA as OFA) (1st ed). Rohtak, India: Ashoka Printers; 2023. p. :64-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of opioid-free anaesthesia on perioperative period: A review. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol. 2020;7:104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Do we feel pain during anesthesia? A critical review on surgery-evoked circulatory changes and pain perception. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31:445-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Are opioids indispensable for general anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:e127-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multimodal general anesthesia: Theory and practice. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1246-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opioid-free anaesthesia: Pro: Damned if you don't use opioids during surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36:247-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in patients after surgery: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:991-1004.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The dark side of opioids in pain management: Basic science explains clinical observation. Pain Rep. 2016;1:e570.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opioid-free anaesthesia. Why and how? A contextual analysis Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38:169-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indications for Opioid Free Anaesthesia and Analgesia, patient and procedure related: Including obesity, sleep apnoea, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, complex regional pain syndromes, opioid addiction and cancer surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anesthesiol. 2017;31:547-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/frank_tallis [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- Available from: https://www.leidos.com/insights/timeline-opioid-epidemic [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- Opioid overdose crisis: Time for a radical rethink. . 2022;7:e195.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New Indian Express. Available from: https://www.msn.com/en-in/lifestyle/family/as-more-children-die-from-fentanyl-some-prosecutors-are-charging-their-parents-with-murder/ar-AA1gsIq7?ocid=wispr&pc=u477&cvid=6dfec09c6f6443f68efafe5c038995fe&ei=62 [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude of substance use in India. 2019. Available from: https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/Survey%20Report636935330086452652.pdf [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Tramadol used in “large numbers” in Punjab and Haryana: HC. Available from: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/punjab/tramadol-used-in-large-numbers-in-punjab-haryana-hc-382240 [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- News. 2019. Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/photos/india-news/photos-tramadol-the-other-opioid-crisis-in-the-developing-world/photo-fOkcjw2Y15JZt85OClWPzH.html [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- The dangerous opioid from India. 2018. Available from: https://www.csis.org/analysis/dangerous-opioid-india [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Opioid-free anaesthesia: The conundrum and the solutions. Indian J Anaesth. 2022;66:S91-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]