Translate this page into:

A large submandibular salivary stone: A case report

*Corresponding author: Grace Budhiraja, Department of ENT, Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences, Bathinda, Punjab, India. drgracebudhirajaadeshent@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Budhiraja G, Kaur N, Dhingra HS, Bharti P, Goyal N. A large submandibular salivary stone: A case report. Adesh Univ J Med Sci Res 2022;4:46-8.

Abstract

Sialolithiasis accounts for the most cases of salivary gland obstruction which leads to recurrent painful swelling of the involved gland which often exacerbates while eating. Stones may be encountered in any of the salivary glands but most frequently in the submandibular gland and its duct. This is a case report of a 40-year-old male patient who had a submandibular sialolith. The sialolith was removed with intraoral approach and no post-operative complications were noted. The article also reviews the various available diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

Keywords

Sialolithiasis

Sialolith

Submandibular gland

INTRODUCTION

Sialolithiasis is the most common disease of salivary glands. It is estimated that it affects 12 in 1000 of the adult population.[1] Males are affected twice as much as females.[2]

Children are rarely affected but a review of the literature reveals 100 cases of submandibular calculi in children aged 3 weeks–15 years old.[3] Sialolithiasis accounts for more than 50% of diseases of the large salivary glands and is thus the most common cause of acute and chronic infections. More than 80% stones occur in the submandibular gland or its duct, 6% in the parotid gland, and 2% in the sublingual gland or minor salivary glands. Multiple calculi in the submandibular gland are rare as are simultaneous lithiasis in more than 1 salivary gland. About 40% of parotid and 20% of submandibular stones are not radiopaque and sialography may be required to locate them. Salivary calculi are usually unilateral and are not a cause of dry mouth. Clinically, they are round or ovoid, rough, or smooth and of a yellowish color. They consist of smaller amounts of magnesium, potassium, and ammonia. This mix is distributed evenly throughout. Submandibular stones are 82% inorganic and 18% organic material whereas parotid stones are composed of 49% inorganic and 51% organic material. The organic material is composed of various carbohydrates and amino acids. Bacterial elements have not been identified at the core of a sialolith.

CASE REPORT

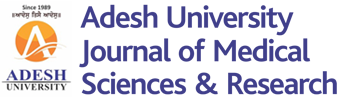

A 40-year-old male presented at the department of otorhinolaryngology for an opinion on a firm mass in the anterior part of the right side of the floor of the mouth. The patient complains of increase in pain during chewing. Extraoral examination revealed a palpable left submandibular gland and intraoral examination revealed a large, firm, and non-tender swelling in the left anterior floor of mouth in the region of the submandibular duct. A diagnosis of the left submandibular duct calculus was made along with the help of CT scan [Figure 1], and at a subsequent appointment, the stone was removed under general anesthetic with sharp dissection through intraoral approach [Figure 2] which was unique in its own kind that such a huge stone [Figure 3] being delivered intraorally through intraoral approach. It measured 30 mm long along its greatest length.

- CT scan showing stone.

- Intraoperative delivery of stone through intraoral approach.

- Delivered specimen (stone).

DISCUSSION

The exact etiology and pathogenesis of salivary calculi are largely unknown. Genesis of calculi lies in the relative stagnation of calcium-rich saliva. They are thought to occur as a result of the deposition of calcium salts around an initial organic nidus consisting of altered salivary mucins, bacteria, and desquamated epithelial cells. For stone formation, it is likely that intermittent stasis produces a change in the mucoid element of saliva, which forms a gel. This gel produces the framework for the deposition of salts and organic substances creating a stone.

Traditional theories suggest that the formation occurs in two phases: A central core and a layered periphery.[3] The central core is formed by the precipitation of salts, which are bound by certain organic substances. The second phase consists of the layered deposition of organic and non-organic material.[4] Submandibular stones are thought to form around a nidus of mucous, whereas parotid stones are thought to form most often around a nidus of inflammatory cells or a foreign body.[5-7] Another theory has been proposed that an unknown metabolic phenomenon can increase the saliva bicarbonate content, which alters calcium phosphate solubility and leads to the precipitation of calcium and phosphate ions. A retrograde theory for sialolithiasis has also been proposed.[8] Aliments, substances, or bacteria within the oral cavity might migrate into the salivary ducts and become the nidus for further calcification. Salivary stagnation, increased alkalinity of saliva, infection or inflammation of the salivary duct or gland, and physical trauma to salivary duct or gland may predispose to calculus formation. Submandibular sialolithiasis is more common as its saliva is (i) more alkaline, (ii) has an increased concentration of calcium and phosphate, and (iii) has a higher mucous content than saliva of the parotid and sublingual glands. In addition, the submandibular duct is longer and the gland has an antigravity flow. Stone formation is not associated with systemic abnormalities of calcium metabolism. Electrolytes and parathyroid hormone studies in patients with sialolithiasis have not shown abnormalities. Gout is the only systemic illness known to predispose to salivary stone formational though in gout, the stones are made predominantly of uric acid. The proposed association between hard water areas and salivary calculi has been shown to be incorrect. The lack of association holds equally for both sexes. One study has suggested a link between sialolithiasis and nephrolithiasis, reporting an association in up to 10% of patients.[6] Calculi may cause stasis of saliva, leading to bacterial ascent into the parenchyma of the gland and, therefore, infection, pain, and swelling of the gland. Some may be asymptomatic until the stone passes forward and can be palpated in the duct or seen at the duct orifice. It may be possible that obstruction caused by large calculi is sometimes asymptomatic as obstruction is not complete and some saliva manages to seep through or around the calculus. Long-term obstruction in the absence of infection can lead to atrophy of the gland with resultant lack of secretory function and ultimately fibrosis. Complete obstruction causes constant pain and swelling, pus may be seen draining from the duct and signs of systemic infection may be present.

Bimanual palpation of the gland itself can be useful, as a uniformly firm and hard gland suggests a hypofunctional or non-functional gland. For parotid stones, careful intraoral palpation around Stenson’s duct orifice may reveal a stone. Deeper parotid stones are often not palpable. When minor salivary glands are involved, they are usually in the buccal mucosa or upper lip, forming a firm nodule that may mimic tumor.

It is very uncommon for patients to have a combination of radiopaque and radiolucent stones; 40% of parotid stones may be radiolucent. Treatment patients presenting with sialolithiasis may benefit from a trial of conservative management, especially if the stone is small. The patient must be well hydrated and can apply moist warm heat and gland massage, while sialogogues are used to promote saliva production and flush the stone out of the duct. With gland swelling and sialolithiasis, infection should be assumed and a penicillinase-resistant anti-staphylococcal antibiotic prescribed. Most stones will respond to such a regimen, combined with simple sialolithotomy when required. Almost half of the submandibular calculi in the distal third of the duct are amenable to simple surgical release through an incision in the floor of the mouth, which is relatively simple to perform and not usually associated with complications. If the stone is sufficiently forward, it can be milked and manipulated through the duct orifice. This can be done with the aid of lacrimal probes and dilators to open the duct. Once open, the stone can be identified, milked forward, grasped, and removed.

The gland is then milked to remove any other debris in the more posterior portion of the duct. The duct may need opening to retrieve the stone. This involves a transoral approach where an incision is made directly onto the stone. In this way, more posterior stones, 1–2 cm from the punctum, can be removed by cutting directly onto the stone in the longitudinal axis of the duct. Care is taken as the lingual nerve lies deep, but in close association with the submandibular duct posteriorly. Subsequently, the stone can be grasped and removed. No closure is done leaving the duct open for drainage. If the gland has been damaged by recurrent infection and fibrosis, or calculi have formed within the gland, it may require removal. Parotid stone management is more problematic as only a small segment of Stenson’s duct is approachable through an intraoral incision. Duct can be complicated by subsequent stenosis of the duct whereas this is rare in the submandibular gland. As a result, parotidectomy is the main stay of surgical management for the majority of intraglandular stones.

CONCLUSION

There are various methods available for the management of salivary stones, depending on the gland affected and stone location. These have been mentioned in the preceding paragraphs. It must be noted, however, that extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy offer alternatives to gland removal. Submandibular gland removal may be indicated following failure of lithotripsy or if the size of an intraglandular stone reaches 12 mm or more as the success of lithotripsy may be <20% in such cases. Parotid gland removal should only be carried out for cases of sialolithiasis resistant to minimally invasive techniques.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Multiple sialolths and a sialolith of unusual size in the submandibular duct. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:331-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Essentials of Oral Pathology Andoral Medicine (6th ed). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. p. :239-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sialolithiasis of the submandibular gland in an 8-year-oldchild. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:188.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New modalities in the management of human sialolithiasis. Mini Invasive Ther. 1994;3:275-84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multiple salivary calculi in Wharton's duct. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99:1313-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A submandibular sialolith of unusual size: A case report. J Otolaryngol. 1991;20:123-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Large calcified mass in the sub maxillary gland. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:679-81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]